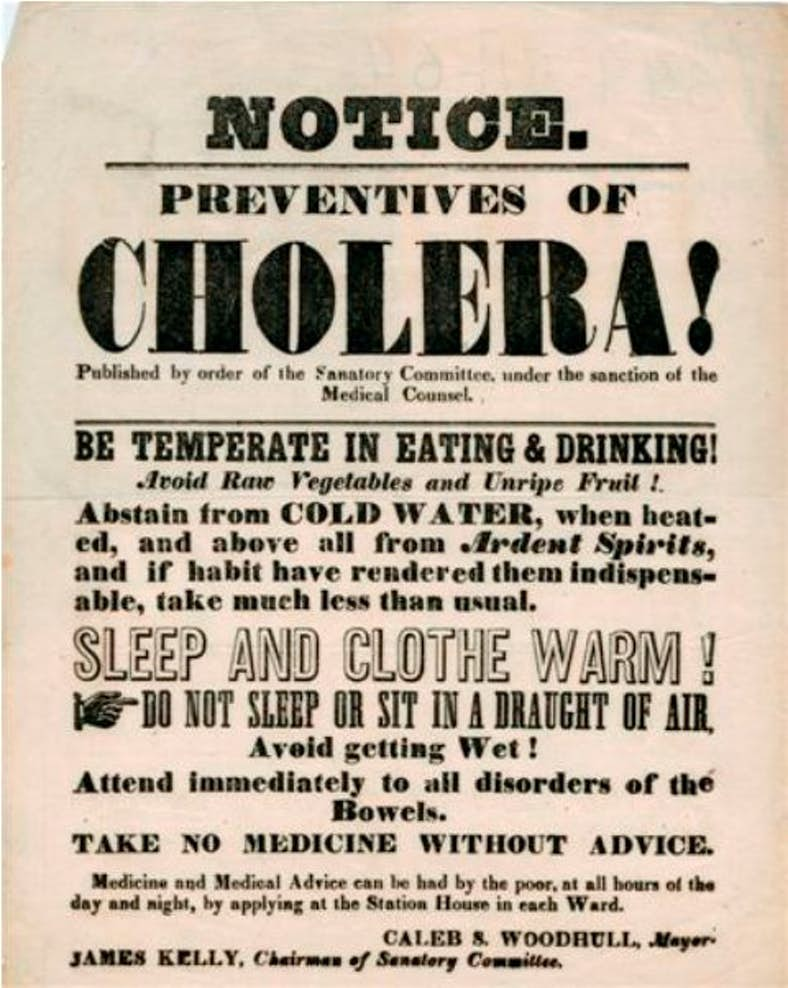

A public notice circa 1832, as ‘Asiatic Cholera’, the first truly global pandemic, gripped New York

A public notice circa 1832, as ‘Asiatic Cholera’, the first truly global pandemic, gripped New York

A thought was bugging me in recent days that Delhi increasingly reminded me of a distant place I knew but couldn’t place. Then it suddenly dawned yesterday when the maid who came to clean the apartment began narrating excitedly that rumours began to spread the previous evening that the ‘subzi mandi’ in her neighbourhood was summarily shut down on ‘Modiji’s orders’.

In no time, slum dwellers rushed to stock up vegetables fearing food shortage in coming days.

Yes, it is the French Algerian city of Oran in the Albert Camus novel The Plague (1947), which also begins like this.

An eeriness is descending over Delhi, which is still nursing the wounds from recent bestial violence. People shrink away, marking distance from you as reports appeared that coronavirus is prowling the city streets.

A mild hysteria broke out in Oran in an April too, when thousands of rats streamed out of their hiding places into the open to spit blood and die. Dr. Rieux then noticed that the concierge of the building where he ran a clinic, M. Michel, died suddenly after falling ill with a fever that had no explanation.

When a few other cases began appearing, Rieux concluded that the city was in the grip of an outbreak of bubonic plague. He and his colleague Castel reported to the authorities, who, of course, were in denial mode and refused to act.

But the denial became unsustainable as a serious epidemic began gripping Oran and the authorities were forced to impose draconian sanitary measures. The entire city was placed under quarantine.

It is not clear to me if the authorities in Delhi ever practised quarantine — leave alone have quarantine legislation, which is prevalent throughout Europe. It is virgin territory for independent India, unless the colonial masters left behind a quarantine code in the light of the waves of choleric epidemic in Bengal that began circa 1817.

Ironically, the credit for refining a quarantine code for human settlements goes to Venice — yes, Italy, which is the epicentre of COVID-19. Venice made the first regulations sometime in mid-15th Century to protect herself from her trade with the Levant, a source of danger at that time.

Most of us have read Camus’ existentialist classic, one of the most riveting literary works on man’s confrontation — and co-habitation — with death. It is a gripping story of raging human passions.

But it can be read at multiple levels as a political allegory on the rise of fascism in Europe or a study of human psychology that might have attracted Alfred Adler (1870-1937), the famous Austrian psychotherapist who is considered the first ‘community psychologist’ — or, personally speaking, a profound exposition of what the existentialist would call the Absurd, our relationship to the absurdity of modern existence.

At the core of Camus’ existential isolation is the discrepancy between the power and beauty of nature, and the desolation of the human condition. We see in his novel man’s mortality in the light of the indifferent vastness of nature.

Rieux, a medical doctor (and the hidden narrator of the novel) chose to battle the pestilence. Although he knew he was powerless against plague, he could bear witness to it when the instinct of most citizens was to slink away.

Compassion — as PM Modi said in his address to the nation on Friday — is what is needed most in the months ahead if there is an outbreak of coronavirus. But, tragically, compassion is in short supply in our ancient capital city, as the horrific violence in recent weeks testified. Iron has entered the Indian’s soul.

But compassion holds the key to Delhi’s success in overcoming the crisis ahead. The plain truth is, we do not know the enemy we are facing.

The Chinese experts warned yesterday about newly discovered symptoms of COVID-19, including diarrhoea, loss of appetite and nausea. In some cases with only diarrhoea, no traces of high fever or coughing are observed.

In Oran, people behaved strangely when the ‘lockdown’ came. Those who got trapped in the imprisonment by sheer coincidence began intensely longing for their absent loved ones.

Father Paneloux took to the pulpit to give a sermon that the plague was God’s wrath, and punishment for man’s sins. But Rambert nonetheless chose to exploit the quarantine by accumulating a great deal of wealth as smuggler.

Meanwhile, Rieux plunged into the battle with death and suffering. His acute sense of ‘powerlessness’ did not prevent him from action.

However, eventually, a terrible beauty was born. As the term of quarantine got extended, many shed their selfish obsession with personal suffering. It dawned on them that they were sailing in a boat of collective disaster on a journey to nowhere with no compass, no navigator.

Out of that cathartic, infinitely humbling experience, the Oran citizen came to terms with his social responsibility.

Yesterday, I read a harrowing account with heavy heart that in the hospitals in Italy, which has the highest number of lives consumed by coronavirus, the number of critically pneumonic patients is far larger than the number of ventilators available to save them, ‘forcing doctors to make the barbaric choice of whom they will try to save and whom they will condemn to death by denying them access to a ventilator.’

‘Staff are shattered … watching patients die alone, without a loved one at their side, often having to say their final farewell over a scratchy cell phone line.’

‘In Bergamo, where the number of dead is rising faster than authorities and churches can bury or cremate them, the Italian government sent a convoy of fifteen army trucks to transport the corpses to other cities for disposal. Loaded with coffins, the trucks drove at night through the city’s deserted streets, filmed only by Bergamo residents confined in apartments overlooking their route.’

When the epidemic ended and Oran broke into wild celebration and a fresh start in life became possible, Rieux, whose wife was dying of a terminal illness that he was powerless to cure , began wondering in the wake of so much suffering and pointless struggle that he and his city went through for several months, whether amidst such hopelessness, there ever could be peace of mind or fulfilment without hope.

He concluded that yes, perhaps there can, for those ‘who knew now that if there is one thing one can always yearn for, and sometimes attain, it is human love’.