Tailors busy stitching Russian flags to meet rising demand in Bamako, the capital of Mali, December 26, 2021

Tailors busy stitching Russian flags to meet rising demand in Bamako, the capital of Mali, December 26, 2021

On Friday, Mali’s transitional government has clarified that it is engaged with Russian military trainers even as French troops are drawing down. So, it is official that Russian security personnel are deployed to Mali.

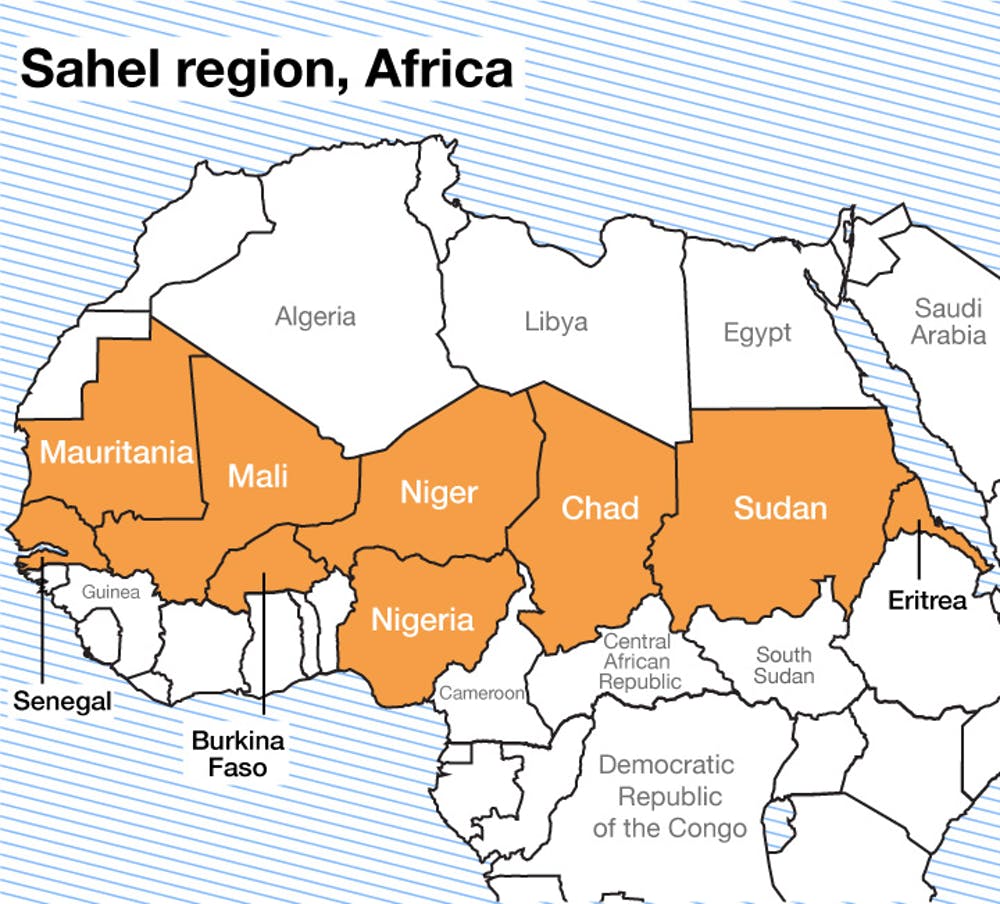

Mali, a landlocked country in the Sahel region in West Africa, is the latest theatre of the great contestation involving the big powers playing out in different forms following the launch of the United States’ containment strategies against China and Russia.

France, the erstwhile colonial power that ruled Mali, and Germany, another colonial power with a violent history in Africa, have been supposedly fighting counterinsurgency in the Sahel region for the past several years.

However, the people of Mali, with good reason, suspect that these European powers are not serious about fighting jihadist groups but are pursuing their neo-colonialist agenda.

Reports have been appearing in the Russian media at least since 2019 that the Sahel countries had sounded out Moscow about the deployment of military advisers, following the model of other regions in Africa such as the Central African Republic.

Sahel region running along the midriff of Africa sits atop some of the largest aquifers on the continent and is potentially one of the richest regions in the world. No doubt, it is a region of great strategic significance, a belt 1,000 km wide that spans the 5,400 km stretch from the Atlantic Ocean to the Red Sea.

In retrospect, the Russian African Economic Forum held on 23-24 October 2019 in Sochi turned out to be an important geopolitical event where the Russian diplomats effectively used history to their advantage.

Historically, Russia carries no colonial backlog in the African continent — unlike France, Britain, Italy, Germany, Portugal or Spain. Russia hasn’t any gory record of making military interventions in Africa — unlike the United States. It has a clean slate — like China.

This history is found very appealing by African elites. Russia has no qualms about acknowledging that Mali government approached it for deputing private companies to boost security in the conflict-torn country.

Earlier this month, Russian Foreign Ministry asserted that Moscow will continue to assist Mali in its fight against terrorism and will further help enhance its army’s combat effectiveness.

The Foreign Ministry said, “Moscow strongly condemns the barbarous act committed by terrorist forces in friendly Mali… We support the Mali government’s intention to take all necessary measures to ensure security, detain and punish those responsible for the crimes.

“Russia will continue to support collective efforts geared to combat terrorism in the Sahara-Sahel region, to offer practical assistance to the countries of this region, including Mali, in terms of enhancing combat effectiveness of their armed forces, training servicemen and law enforcers.”

On its part, Mali too plays with an open hand. In his address to the UN General Assembly in September, Mali’s Prime Minister Choguel Kokalla Maiga accused France of abandoning his country with its “unilateral” decision to withdraw troops. The French President Macron’s predicament is that his five-nation war across Africa’s Sahel region is as unpopular in Mali as it is at home in France.

Meanwhile, Malians have given a rapturous welcome to the Russian military advisors. France 24 reported that the tailors in Bamako, the capital and largest city of Mali, are doing roaring business making Russian flags to meet the local demand.

France’s 10-year old war has devastated Mali and several other countries, but has failed to contain the threat from the Muslim rebel groups affiliated with al-Qaeda and Islamic State that incubated in next-door Libya following the NATO-directed regime change project to overthrow Muammar Gaddafi in 2011, which was, ironically enough, piloted by France only.

Like with the US occupation of Afghanistan, suspicions have arisen that France has been playing a dubious game in Mali. In October, Prime Minister Choguel Kokalla Maïga told the Russian media that French forces have been secretly funnelling support to terrorist groups like the al-Qaeda-aligned Ansar el-Din front and had no intention of winning the war.

In reality, Macron is only ordering a partial withdrawal of troops. Most of the 5,000 French troops deployed in Mali are merely shifting south, toward the tri-border area with Burkina Faso and Niger. France has no intentions of abandoning Sahel although its reputation is in the mud among the local people. Its neocolonial agenda is self-evident.

Indeed, Mali holds rich deposits of gold, bauxite, manganese, iron ore, limestone, phosphates, uranium, etc. Gold dominates Mali’s mineral sector; Mali is 4th largest gold producer in Africa. Mali’s mineral resources remain relatively undeveloped; its territory remains largely unexplored and unmapped.

The Europeans are seething with envy and fury that the Russians may establish themselves in Mali and replace them for good. Last Thursday, France and 15 NATO allies issued a joint statement denouncing the Mali government’s invitation to the Russian security personnel. Interestingly, the US issued a separate statement.

The fact of the matter is that NATO has been planning to move into Sahel to provide a platform for the western powers to concentrate on their neo-colonial agenda to exploit the resources of that region. But the project is stalled since the gateway to Sahel is Libya where anarchical conditions prevail (and Russia has an established presence already.)

If Russian were to spread wings in the Sahel region as well, the NATO might as well mothball its African dreams once and for all.

As it is, the Western powers desperate about the inroads China is making in the African continent. China lists 39 African countries on the Belt and Road official website, ranging geographically from Tunisia to South Africa. China has lent African countries hundreds of billions of dollars as part of Belt and Road Initiative.

The BRI is often critiqued by its detractors as so-called “debt trap diplomacy.” But BRI projects in Africa reveal a nuanced reality of how the initiative functions in the developing world, where infrastructure financing is desperately needed, and political externalities are of secondary concern to the receiving states.

China’s courtship of African political and military leaders through visits from top Beijing leadership has been absolutely outstanding. Equally, it creates space for the African elites to negotiate with the erstwhile colonial powers in Europe.

The noted American scholar Yun Sun, a director at the Stimson Center in Washington, said in a Congressional testimony on China’s presence and investment in Africa that “China’s strategic aspirations are causally related to its economic engagement in Africa and are mutually reinforcing each other.” That is a perceptive observation.

It is in this context that the paranoia of the Western powers is to be understood — that Russia may be effectively complementing the Chinese challenge which is already formidable. Succinctly put, the West’s neo-colonialist agenda is being checkmated. The profound economic and strategic implications cannot be overstated.

This is not to suggest that Russia and China are acting in concert in Mali, although it is conceivable that they could be coordinating and are, most certainly, on the same page. The stakes are high insofar as Mali sits on great untapped mineral wealth.

Unlike China which sticks to business deals, Russia does not shy away from declaring its unflinching support for the struggle against all neo-colonial tendencies in Africa.