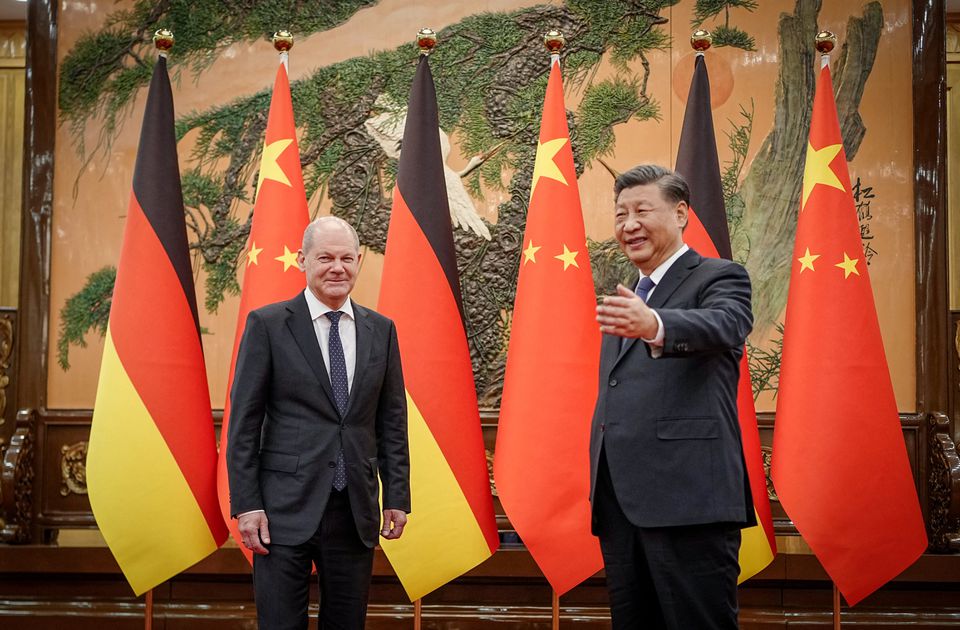

Chinese President Xi Jinping (R) received German Chancellor Olaf Scholz at Great Hall of the People, Beijing, November 4, 2022

Chinese President Xi Jinping (R) received German Chancellor Olaf Scholz at Great Hall of the People, Beijing, November 4, 2022

German diplomacy presented a riveting sight of “counterpoint” with Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock hosting her G7 partners in Münster on November 3-4 even as Chancellor Olaf Sholz was emplaning from Berlin on a one-day visit to Beijing.

The photo-op showed the US Secretary of State Antony Blinken flanking Baerbock at the main table with Under-secretary of State Victoria Nuland — best known as the master of ceremonies at the 2014 “Maidan” coup in Kiev in 2014 — peering from behind.

Germany is catching up with photo journalism. Seriously, the photo couldn’t have arrested more meaningfully for the world audience the split personality of German diplomacy as the present coalition government pulls in different directions.

Quintessentially, Baerbock has highlighted her discontent with Scholz’s China visit by assembling around her the like-minded G7 counterparts. Even by norms of coalition politics, this is an excessive gesture. When a country’s top leader is on a visit abroad, a display of dissonance undercuts the diplomacy.

Equally, Baerbock’s G7 counterparts chose not to wait for Scholz’s return home. Apparently, they have a closed mind and the tidings of Scholz’s discussions in Beijing will not change that.

First thing on Monday, Scholz should ask for Baerbeck’s resignation. Better still, latter should submit her resignation. But neither is going to happen.

In the run-up to Scholz’s China visit, he faced withering criticism for undertaking such a mission to Beijing with a business delegation of powerful German CEOs. Clearly, the Biden Administration looked up to Baerbock and the influential “Atlanticist” circles embedded within Germany’s political economy to lead the charge.

Has Scholz bitten more than he could chew? The answer depends on a counter question: Is Scholz eyeing a legacy in the great tradition of his predecessors in the Social Democratic Party, Willy Brandt (1969-1974), Helmut Schmidt (1974-1982)?

Those two titanic figures took path-breaking initiatives toward the former Soviet Union and China respectively during defining moments in modern history, defying the shackles of Atlanticism that curbed Germany’s strategic autonomy and consigned that country as a subaltern in the US-led alliance system.

The cardinal difference today is that Brandt (who navigated Ostpolitik ignoring the furious American protestations over the first-ever gas pipeline connecting Soviet gas fields with Germany) and Schmidt (who seized the moment to cash in on US-China normalisation) — and Chancellor Gerhard Schroeder (1998-2005) too, who expanded and deepened expansion of business relations with Russia and struck an unprecedented working relationship with the Kremlin leadership, much to Washington’s irritation — were assertive leaders.

Put differently, it all depends on Germany’s collective will to break the NATO glass ceiling, which Lord Ismay, the Alliance’s first secretary-general, had succinctly captured as intended to “to keep the Soviet Union out, the Americans in, and the Germans down.” Currently, the interplay of three factors impact German politics.

First, the Indo-Pacific strategy. Make no mistake, the proxy war in Ukraine is a dress rehearsal for the inevitable confrontation between the US and China over Taiwan issue. In both cases involving the strategic global balance, the stakes are exceedingly high for the US’ global hegemony and the multipolarity in the world order.

Germany has a pivotal role in this epochal struggle, not only by virtue of occupying the highly volatile ground in the middle of Europe that also carries remains of history, but being the economic powerhouse in the continent at the threshold of becoming a superpower.

The angst in Washington is self-evident that Scholz’s China visit may weaken the US’ geopolitical design to repeat the impressive feat of western unity over Ukraine if tensions boil over in Asia-Pacific and China is forced to act.

Of course, no analogy is complete as China is unlikely to opt for a 9-month old, incremental special military operation by Russia to “grind” the Taiwanese military and destroy the Ukrainian state. It’ll be world war from day one.

The analogy is complete, though, when it comes to the sanctions from hell that the Biden Administration will impose on China and the brigandry of confiscation of China’s “frozen assets” (exceeding a trillion dollars at the very least) ensues, apart from paralysing China’s supply chains.

Suffice to say, “doing a Ukraine” on China holds the key to the perpetuation of US global hegemony, as China’s financial assets get appropriated to refuel America’s ailing economy and dollar’s status as world currency and neo-mercantalism and control of capital movement, etc. remain intact.

Second, one big diplomatic victory of the Biden Administration so far has been in transatlantic politics where it succeeded in consolidating its dominance over Europe by pitchforking to the centerstage the Russia question. The European countries’ Manichean fears of a historic resurgence of Russian power were stirred up.

Few expected a Russian resurgence so soon after President Vladimir Putin’s famous speech at the Munich Security Conference in February 2007.

The western narrative at that time was that Russia simply lacked the capacity to regenerate as a global power, as Russia’s military’s modernisation was unfeasible. Arguably, Chancellor Angela Merkel’s entire diplomacy toward Russia (2005-2021) was pinned on that facile narrative.

Thus, when Putin announced most unexpectedly at a meeting of the Defence Ministry Board in Moscow on 24th December 2019 that Russia has become world leader in hypersonic weaponry and that “not a single country possesses hypersonic weapons, let alone continental-range hypersonic weapons,” the West heard it with undisguised horror.

The Biden team cashed in on the profound disquiet in the European capitals to rally them and drum up “western unity” over Ukraine. But a hairline crack is now appearing over Scholz’s visit to Berlin. Blinken rushed in to pull Scholz back into the fold.

Third, following the above, a fundamental contradiction has appeared today as the West’s “sanctions from hell” against Russia boomeranged on Europe, pushing it into recession. Germany has been hit very hard, and is staring at the spectre of the collapse of entire sectors of its industry, consequent unemployment and social and political turmoil.

The German industrial miracle was predicated on the availability of cheap, unlimited, assured supply of energy from Russia, and the disruption is creating havoc. On top of it, the sabotage of Nord Stream pipelines rules out a revival of the energy nexus between Germany and Russia (which German public opinion favours.)

To be sure, with all the data available from the sea bed in the Baltic Sea, Schulz must be well aware of the geopolitical implications of what the US has done to Germany. But he is not in a position to create a ruckus and instead opted to internalise the sense of bitterness, especially as Germany is in a humiliating position today of having to buy frightfully expensive LNG from American companies to replace Russian gas (which the US is marketing in Europe at prices three to four times that of the domestic price.)

The only option left to Germany is to reach out to China in a desperate search to revive its economy. Incidentally, Scholz’s mission primarily aimed at the relocation of production units of BASF, the German multinational chemical company and the largest chemical producer in the world, to China so that its products remain competitive.

It is highly improbable, though, that Washington will allow Scholz a free hand. Fortuitously for Washington, Scholz’s coalition partners — the environmentalist Green Party and the neo-liberal Free Democrats (FDP) — are unvarnished atlanticists and are willing to play the American game, too.

Brandt or Schroeder would have fought back, but Scholz is not a street fighter, although he senses the US’ grand design to transform Germany as an appendage of the American economy and integrate it into a single supply chain. Simply put, Washington expects Germany to be an indispensable cog in the wheel of the collective West.

Meanwhile, Washington holds a strong hand, as Germany’s corporate sector is also a divided house with many companies who are well-placed to benefit from the economic model shift that Washington is promoting, showing reluctance to support Scholz — albeit he’s a corporatist chancellor himself.

The US is adept at leveraging such situations of “divide-and-rule”. Reportedly, some of Germany’s high-tech companies did not accept Scholz’s invitation to accompany him to Beijing, including the CEOs of Mercedes-Benz, Bosch, Continental, Infineon, SAP, and Thyssen Krupp.