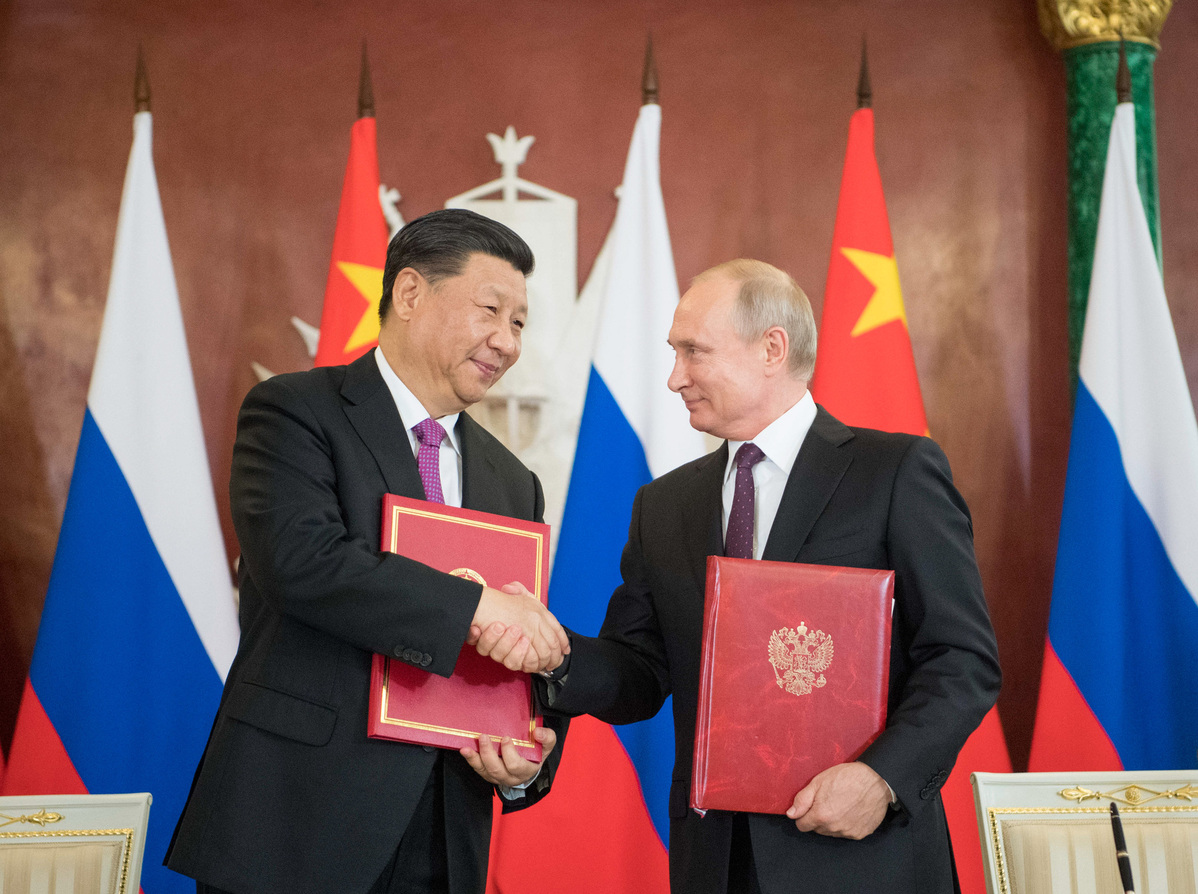

Russian President Vladimir Putin (R) and Chinese President Xi Jinping (R) signed the statements on the “comprehensive strategic partnership of coordination for a new era” and on “strengthening contemporary global strategic stability”, Moscow, June 5, 2019

Russian President Vladimir Putin (R) and Chinese President Xi Jinping (R) signed the statements on the “comprehensive strategic partnership of coordination for a new era” and on “strengthening contemporary global strategic stability”, Moscow, June 5, 2019

The first part of the three-part essay is here. The second part is here.

Discourse of shared legacies

The disintegration of the former Soviet Union in 1991 was a geopolitical disaster for Russia. But the watershed event, paradoxically, prompted Moscow and Beijing, erstwhile adversaries, to draw closer together, as they watched with disbelief the United States’ triumphalist narrative of the end of the Cold War, overturning the order they both had regarded, despite all their mutual differences and disputes, as crucial for their national status and identities.

The Soviet collapse resulted in great uncertainty, ethnic strife, economic deprivation, poverty, and crime for many of the successor states, in particular for Russia. And Russia’s agony was closely observed from across the border, in China. The policymakers in Beijing studied the experience of Soviet reforms in order to steer clear of the “tracks of an overturned cart.” A sense of apprehension over the Soviet collapse might have been there, stemming from the shared roots of the two countries’ modernities.

But, looking back, whilst the political discourses in China and Russia on the reasons for the disintegration of the Soviet Union would have shown at times divergent outlooks, the leaderships in Moscow and Beijing succeeded in ensuring that the future of their relationship remained impervious to it.

Soon after becoming the general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party, Xi Jinping is known to have spoken about the former Soviet Union. The first time was in December 2012, when, in comments to party functionaries, he reportedly remarked that China still had to “profoundly remember the lesson of the Soviet collapse.” He went on to talk about “political corruption,” “thought heresy,” and “military insubordination” as reasons for the decline of the Soviet Communist Party. Xi reportedly said, “One important reason was that ideals and beliefs were shaken.” In the end, Mikhail Gorbachev just uttered a word, declaring the Soviet Communist Party defunct, “and the great party was gone just like that.”

Xi said, “In the end, there was not a man brave enough to resist, no one came out to contest (this decision).” A few weeks later, Xi revisited the topic and reportedly said that one important reason for the Soviet collapse was that the struggle in the ideological sphere was extremely fierce; there was a complete denial of Soviet history, denial of Lenin, denial of Stalin, pursuit of historical Nihilism, confusion of thought; local party organisations were almost without a role. The military was not under the Party’s oversight. “In the end, the great Soviet Communist Party scattered like birds and beasts. The great Soviet socialist nation fell to pieces. This is the road of an overturned cart!”

In the Russian narrative, the main reason was the failure of the Soviet macro-economic policy. It is easy to see why President Vladimir Putin appeals to China’s experience of reform and opening. Putin does not claim to be a Marxist-Leninist; nor does he draw on the Soviet ideology for legitimacy. In his perspective, perestroika was well-founded as Gorbachev clearly understood that the Soviet project had run aground. But Gorbachev’s new ideas and new policies failed to deliver and led in turn to a deep economic crisis and financial insolvency that ultimately discredited him and destroyed the Soviet state.

Putin had first-hand experience of both the wonders of Soviet socialism as well as its fatal failure to compete with the West in providing the quality of life for the citizens. Probably, Putin returned to St. Petersburg from his post in Dresden utterly disenchanted with communist ideals. Putin was not quite five months old when Stalin died, and for him, the great figures of Marxism-Leninism didn’t add up to much.

On the other hand, Xi Jinping experienced China in the grip of a revolution. For Xi, Mao was both a god-like figure and a living person. Xi’s own father was Mao’s comrade (even if Mao purged him). Xi experienced the Cultural Revolution first-hand. Yet, for him, denying Mao would be like denying a part of himself. Therefore, Xi’s rejection of Soviet-style “historical Nihilism” comes naturally to him. In Xi’s words, “The Soviet Communist Party had 200 thousand members when it seized power; it had 2 million members when it defeated Hitler, and it had 20 million members when it relinquished power… For what reason? Because the ideals and beliefs were no longer there.”

But where Putin and Xi Jinping come together is in three things. One is their shared appreciation of China’s astonishing sprint to the ranks of an economic superpower. In Putin’s words, China “managed in the best possible way, in my opinion, to use the levers of central administration (for) the development of a market economy… The Soviet Union did nothing like this, and the results of an ineffective economic policy impacted the political sphere.” The great importance — almost the centrality — that Putin attaches to the economic ties in the overall Sino-Russian partnership falls into perspective.

Second, despite whatever differences there might be in the respective narratives of the two countries regarding the reasons for the Soviet collapse, Putin and Xi are on the same page on the legitimising discourse of revolutionary greatness that the Soviet Union represented. Thus, the Sino-Russian identity is very much on display today in their common stance against the West’s attempts to falsify the history of the World War 2.

In a recent interview, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov said, “we are witnessing an aggression against history aimed at revising the modern foundations of international law that were formed in the wake of World War 2 in the form of the UN and the principles of its Charter. There are attempts to undermine these very foundations. They are primarily using arguments that represent an attempt to equate the Soviet Union with Nazi Germany, aggressors who wanted to enslave Europe and turn the majority of the peoples on our continent into slaves with those who overcame the aggressors. We are being insulted by outright accusations that the Soviet Union is more culpable for unleashing WW2 than Nazi Germany. At the same time, the factual side of the matter, such as how it all began in 1938, the policy of appeasing Hitler by the Western powers, primarily France and Great Britain, is thoroughly swept under the rug.”

A model alliance of mutual support

China is also experiencing currently a similar trajectory of role reversal — the aggressor becoming preachy and the victim being pilloried. A strong sense of empathy with Russia on the part of China is only natural as it too faces predicaments such as being forced to the back foot on the issue of human rights in Xinjiang or being branded as “assertive” when it began reviving in 2015 its historical claims in the South China Sea from where they were abandoned in 1935, in response to the activities of the other littoral states.

It is an open secret that the western intelligence had a big hand in stirring up the unrest in Hong Kong. In fact, the history of the US interference in China’s internal affairs to destabilise the communist government is not new. It goes back to the CIA’s covert activities in Tibet in the fifties and early sixties (which was partly at least responsible for triggering the 1962 China-India conflict). Today, the US is steadily backtracking on its “One-China” policy, which was the bedrock of the Sino-American normalisation in the early 1970s.

Similarly, the US interference in Russian politics that began surging through the late 1980s in the Gorbachev era became blatant and obtrusive in the 1990s following the collapse of the former Soviet Union. The US openly engineered a desired outcome in favour of Boris Yeltsin in the Russian presidential election in 1996 — and has openly bragged about financing it and micro-managing it.

Putin has accused the United States of stirring up protests in Russia in 2011 and spending hundreds of millions of dollars to influence Russian elections. Putin said that then US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton had encouraged “mercenary” Kremlin foes. “She set the tone for some opposition activists, gave them a signal, they heard this signal and started active work,” he alleged.

Invoking Ukraine’s 2004 Orange Revolution and the violent downfall of governments in Kyrgyzstan, Putin has said Western nations were spending heavily to foment political change in Russia. “Pouring foreign money into electoral processes is particularly unacceptable. Hundreds of millions are being invested in this work. We need to work out forms of protection of our sovereignty, defence against interference from outside.” Putin added, “What is there to say? We are a big nuclear power and remain so. This raises certain concerns with our partners. They try to shake us up so that we don’t forget who is boss on our planet.”

The pattern of interference by the US and its close allies was much the same in Hong Kong — to destabilise China and thwart its rise as a global power. Equally, China faces today the very same pattern Russia experienced of the US creating a network of hostile states surrounding it, encircling it — Georgia, Ukraine, Poland, the Baltic States, etc. Last week, the director of Russia’s foreign intelligence service SVR, Sergey Naryshkin stated that Washington had provided about $20 million for staging anti-government demonstrations in Belarus.

Naryshkin said, “According to the available information, the United States is playing a pivotal role in the current events in Belarus. Though publicly Washington tries to keep a low profile, once the massive street demonstrations began, the Americans stepped up funding to the Belarusian anti-government forces bountifully to the tune of tens of millions of dollars.”

He specified, “The demonstrations have been well organised from the very outset and coordinated from abroad. It is noteworthy that the West had launched the groundwork for the protests long before the elections. The United States in 2019 and early 2020 used various NGOs to provide about $20 million for staging anti-government demonstrations.”

Belarus, of course, is the missing link in the arc of encirclement of Russia that the US contrived to put in place. The very same approach is today at work against China, too. The US-led Quadrilateral Alliance (Quad) comprising Japan, India and Australia serve such a purpose.

In earlier years, the Russian-Chinese entente focused exclusively on the bilateral relationship. Incrementally, it moved on to coordination at the foreign-policy level — in a limited way, to begin with — which has steadily intensified.

Russia and China are helping each other to push back at the US’ containment policies. Thus, China has openly hailed the election victory of Belarus president Alexander Lukashenko. On Russia’s part too, there is much louder criticism of the US attempts to ratchet up tensions in the Asia-Pacific. Foreign Minister Lavrov said on September 11 in Moscow in the presence of the visiting Chinese State Councilor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi,

“We noted the destructive character of Washington’s actions that undermine global strategic stability. They are fuelling tensions in various parts of the world, including along the Russian and Chinese borders. Of course, we are worried about this and object to these attempts to escalate artificial tensions. In this context, we stated that the so-called “Indo-Pacific strategy” as it was planned by the initiators, only leads to the separation of the region’s states, and is therefore fraught with serious consequences for peace, security and stability in the Asia-Pacific Region. We spoke in favour of the ASEAN-centric regional security architecture with a view to promoting the unifying agenda, and the preservation of the consensus style of work and consensus-based decision-making in these mechanisms… We are seeing attempts to split the ranks of ASEAN members with the same aims: to abandon consensus-based methods of work and fuel confrontation in this region.”

Again, on September 18, in an interview with Nikkei Asian Review in Washington, Russian ambassador to the US Anatoly Antonov stated, “We believe that the US attempts to create anti-Chinese alliances around the world are counterproductive. They present a threat to international security and stability… As for the US policy in Asia-Pacific, …Washington promotes anti-Chinese sentiments and its relations with regional countries are based on their support to such an approach… It is difficult to call the Indo-Pacific initiative ‘free and open.’ More likely it is quite the opposite: this project is non-transparent and non-inclusive… if we talk about the Indian Ocean countries. Instead of well-established norms of the international law Washington promotes there an obscure ‘rules based order.’ What are those rules, who created them and who agreed to them – all this remains unclear.”

These statements suggest that in actual fact, a steady evolution is taking place in the Russian attitude even as the US is ratcheting up pressure on China in the South China Sea and East China Sea.

Foundation for mutual trust

The western propagandists blithely overlook that the Sino-Russian alliance is built on strong foundations. Do not forget for a moment that Xi Jinping’s first overseas visit as president of was to Russia — in March 2013, a full year ahead of the Ukraine crisis that led to western sanctions against Moscow. Yet, the western analysts insist that the Russian-Chinese entente was a “pivot” by Russia, ensuing from its estrangement with Europe.

Speaking ahead of the visit to Russia, Xi said the two countries were “most important strategic partners” who spoke a “common language”. Xi called Russia a “friendly neighbour”, and said that the fact that he was visiting so soon after assuming presidency was “a testimony to the great importance China places on its relations with Russia. China-Russia relations have entered a new phase in which the two countries provide major development opportunities to each other.”

In an interview with Russian press on the occasion of Xi’s visit, Putin said Russia-China co-operation would produce “a more just world order”. Russia and China, he said, both demonstrated a “balanced and pragmatic approach” to international crises. (In an article in 2012, Putin had called for further economic co-operation with China to “catch the ‘Chinese wind’ in (its) economic sails”.)

One significant outcome of Xi’s talks with Putin was the formalisation of a direct contact between the two high offices in Moscow and Beijing. In July 2014, Sergei Ivanov, then Chief of Staff of the Presidential Executive Office in the Kremlin and Li Zhanshu, then Head of the Secretariat of the Chinese Communist Party Central Committee institutionalised this format when the former visited Beijing.

That was the first ever such format of contact for the Chinese side directly with another country. Li and Ivanov (who was received by Xi Jinping in Beijing) drew up the road map for a multifaceted relationship riveted on intensive top level contacts, and cemented the strategic partnership.

Four years later in a September 2019 visit to Moscow in his new position as Chairman of the Standing Committee of the Chinese National People’s Congress, Li Zhanshu said at a meeting with Putin in the Kremlin, “Nowadays, the US is carrying out double containment of China and Russia, as well as trying to sow discord between us, but we can see this very well and will not take that bait. The main reason is that we have a very solid foundation for mutual political trust. We will continue strengthening it and firmly support each other’s aspiration to walk down the path of our own development, as well as defending national interests and ensuring the sovereignty and security of the two countries.”

Li told Putin, “In the last few years, our relations have reached an unprecedentedly high level. It was possible primarily because of strategic leadership and personal effort of the two leaders. Chinese President Xi Jinping and you are great politicians and strategists who think globally and broadly.”

In fact, the joint statement signed by Xi Jinping and Putin on June 5 last year in Moscow during the Chinese leader’s state visit to Russia was widely noted as a pivot that elevated the relationship to the new connotation of the China-Russia “comprehensive strategic partnership of coordination for a new era”.

A Chinese commentator Kong Jun writing in the People’s Daily at that time described the June 2019 statement as showcasing “the maturing of a relationship featuring the highest degree of mutual trust, the highest level of coordination and the highest strategic value.” Simply put, Xi’s state visit Russia last year signalled that the two countries were on the threshold of building allied relations de facto though not de jure.

A functional military alliance was in the making too by that time. Exactly three months after Xi’s state visit to Russia, Putin spoke publicly for the first time about an “alliance” with China — precisely, in front of a domestic audience on September 6, 2019, in Vladivostok. Since then, of course, the messages exchanged between the Russian and Chinese leaders routinely began to underscore their pledge and firm determination to jointly safeguard “global strategic stability”, as enunciated in the June 2019 joint statement issued after Xi’s state visit.

In October last year, hardly four months after Xi’s state visit to Moscow, while addressing a political conference in Sochi, Putin dropped a bombshell. He disclosed, “We are currently helping our Chinese partners to create a missile attack warning system. It is a serious thing that will drastically increase the defence capabilities of the People’s Republic of China. Right now only the US and Russia have such systems.”

A day later, Putin’s spokesman Dmitry Peskov lauded Russia’s “special relations, advanced partnership with China … including in the most sensitive (areas) linked to military-technical cooperation and security and defence capabilities.” Separately, Sergei Boyev, director general of Vympel, Russia’s major weapons manufacturer, confirmed to the state-run media that the company was working on “modelling” the missile attack warning system for China. “We can’t talk in detail about it because of confidentiality agreements,” Boyev said.

Alliance for global strategic stability

Putin’s speech in Sochi in October was hugely significant where he lauded the “unprecedented level of mutual trust and cooperation in an allied relationship of strategic partnership” between Russia and China. Putin noted that the missile-attack early warning system (Systema Preduprezdenya o Raketnom Napadenii — SPRN) will be “seriously expanding the PRC’s defence capabilities.”

Also, Putin denounced as futile the US attempts to contain China through economic pressure and by building up Asia-Pacific alliances (Quad) with other regional states. Commenting on Putin’s speech, the pro-Kremlin news site Vzglad flagged that while Moscow and Beijing will not be signing a formal political-military alliance treaty anytime soon, the two countries are de facto allies already, closely coordinating their activities in different areas, building together a new world order that may lead to the eviction of US influence from Asia.

The strategic import of Russia’s transfer of advanced missile early-warning knowhow to China needs to be properly understood. It implied a virtual military alliance. It coincided with a massive Russian military exercise, dubbed Center-2019 (Tsentr-2019), held from September 16 to 21 in Western Russia to which PLA’s Western Theater Command had dispatched an undisclosed number of Type 96A main battle tanks, H-6K strategic bombers, JH-7A fighter bombers, J-11 fighter jets, Il-76 and Y-9 transport aircraft, and Z-10 attack helicopters.

On the Russian side, the exercise reportedly involved 128,000 servicemen, over 20,000 pieces of hardware including 15 warships, 600 aircraft, 250 tanks, about 450 infantry fighting vehicles and armoured personnel carriers, and up to 200 artillery systems and Multiple Launch Rocket Systems. The Russian MOD stated that the main objectives of the strategic command post exercise was to verify readiness levels of the Russian military and to improve interoperability.

As far back as May 2016, Russia and China had begun their first simulated computer anti-missile defence exercises. An announcement in Moscow at that time described it as “the first joint Russian-Chinese computer-enabled command-staff anti-missile defence exercises”, which was held at the scientific research centre of Russian Aerospace Defense Forces.

The Russian Defense Ministry explained that the exercises’ main goal was to drill “joint manoeuvers and operations of rapid reaction anti-aircraft and anti-missile defence units of Russia and China in a bid to defend the territory from occasional and provocative strikes by ballistic and cruise missiles”. It said, “The Russian and Chinese sides will use the results of the exercises to discuss proposals on Russian-Chinese military cooperation in the field of anti-missile defence.”

Therefore, suffice to say, the transfer of the SPRN was far from a “stand alone” event. In plain terms, this is about Russia providing China with an exclusive know-how to both counter US missile strikes as well as to develop “second strike capability” that is crucial to the maintenance of strategic balance.

The SPRN consists of powerful long-range radars with the capability to detect incoming ballistic missiles and warheads. If China buys the more powerful and longer-range S-500 anti-missile system (which Russia is beginning to produce and deploy) in addition to the S-400s, Russia would be in a position to help China build and influence the architecture of a future integrated PLA SPRN and missile-defence capability that will represent for China a strategic stabilising factor vis-a-vis the US, providing reliable information on potential American missile launches and calculate their possible impact points.

Plainly put, the Russian system can guarantee for the leadership in Beijing “tens of minutes” of reliable early warning of an imminent enemy missile strike before impact, allowing for appropriate decisions to launch China’s nuclear missiles in a reply salvo.

Clearly, this is a prelude to Russia’s deeper cooperation with China on creating an integrated missile defence system. Importantly, it signifies that Russia is creating a military alliance with China and raising the stakes should the US decide to attack either. A Moscow-based foreign affairs analyst Vladimir Frolov told CBS News, “If the Chinese missile attack warning system will be integrated with Russia’s, we will get increased detection range for the US ballistic missiles launched from submarines in the South Pacific and Indian Ocean, where we have problems with fast detection.”

To be sure, the Russia-China alliance is far more nuanced than it first appears. In a rare display of warm personal relations, Xi said in an interview with Russian media ahead of his trip to Russia in June last year, ”I have had closer interactions with President Putin than with any other foreign colleague. He is my best and bosom friend. I cherish dearly our deep friendship.” At a ceremony in the Kremlin during the visit, marking the 70th anniversary of Russian-Chinese diplomatic ties, Xi told Putin that China was “ready to go hand in hand with you.”

Xi said, “The Russian-Chinese relations, which are entering a new stage, are based on solid mutual trust and strategic bilateral support. We need to cherish the precious mutual trust. We need to boost bilateral support in matters that are critically important to us, to firmly maintain the strategic direction of Russian-Chinese relations despite all kinds of interference and sabotage. The Russian-Chinese relations, which are entering a new era, serve as a reliable guarantee of peace and stability on the globe.”

Conclusion

The US National Security Strategy document dated December 2017, the first of its kind in the Trump presidency, characterised Russia and China as “revisionist” powers. The concept of revisionism is flexible enough to hold various meanings that typically distinguish between states that accept the status quo distribution of power in the international system and those which seek to alter it to their advantage.

Quintessentially, Russia and China contest a set of neoliberal practices that have evolved in the post-World War 2 international order validating selective use of human rights as a universal value to legitimise western intervention in the domestic affairs of sovereign states. On the other hand, they also accept and continuously affirm their commitment to a number of fundamental precepts of the international order — in particular, the primacy of state sovereignty and territorial integrity, the importance of international law, and the centrality of the United Nations and the key role of the Security Council.

Critically, Russia and China have acted as rule takers rather than challengers in their participation in the global financial institutions. China is a leading exponent of globalisation and free trade. In sum, Russia and China’s view of the operation of the international system conforms in a large part to Westphalian precepts.

In geopolitical terms, nonetheless, the US National Security Strategy document of December 2017 says, “China and Russia challenge American power, influence, and interests, attempting to erode American security and prosperity… China and Russia want to shape a world antithetical to U.S. values and interests. China seeks to displace the United States in the Indo-Pacific region… Russia aims to weaken U.S. influence in the world and divide us from our allies and partners… Russia is investing in new military capabilities, including nuclear systems that remain the most significant existential threat to the United States.”

Admittedly, the previous “model alliance” between Russia and China has evolved into a “real alliance” today. The internal dynamics of China-Russia relations has become increasingly strong and exceeds any influences from the external international enviornment. The expanding strategic partnership has already brought comprehensive benefits to both countries and has become a common strategic asset. At the same time, it strengthens their respective status on the international stage and provides basic support for the diplomacy of both countries.

The heart of the matter is that the Russia-China alliance does not conform to the norms of a classic alliance system. For want of a better way of characterising it, one may call it a “plug-in” alliance. In the normal life, it can perform a range of “customisable options” while also provide support for any specific functionality that may arise. It enjoys a great deal of flexibility. The Russia-China alliance has no intention to militarily confront the US. But its posturing is geared to deter a US attack on either, or both. Simply put, a race of attrition is on. And it is going to be more and more frustrating for the US, as Russia has lately moved in to challenge the so-called “Indo-Pacific strategy”.

The Russian criticism of “Indo-Pacific strategy” has become strident. This is happening at a time when tensions are rising in the Taiwan Straits and the Quad plans to hold a meeting for the first time in Japan in October.

On September 17, the Kremlin expressed alarm that “the military activities of non-regional powers” (read the US and its allies) are causing tensions and the Eastern Military District based in Khabarovsk, one of Russia’s four strategic commands, is being reinforced with a mixed aviation division command unit and an air defence brigade.

The US cannot win this contestation by its very nature. The Quad is useless since three out of its four members — Japan and India — have no reason to regard Russia as a revisionist power or to be hostile toward it. Some American pundits say the answer lies in the US reverting to its transatlantic ties, which Trump neglected, and Biden can energise Euro-Atlanticism in Europe overnight. But that is not as simple as it sounds.

The point is, as the former German Foreign Minister Joschka Fischer once wrote, the growing transatlantic “rift” is borne out of an alienation — a mix of disagreements, lack of mutual trust and respect, and divergent priorities — that dates back to the pre-Trump era, and it will not end even after a new incumbent enters the White House. Besides, there are many European states who do not share the US’ hostility toward Russia and China.

The paradox of the Sino-Soviet alliance lies here. The US cannot overwhelm that alliance unless it defeats both China and Russia together, simultaneously. The alliance, meanwhile, also happens to be on the right side of history. Time works in its favour, as the decline of the US in relative comprehensive national power and global influence keeps advancing and the world gets used to the “post-American century.”

Clearly, the leaderships in Moscow and Beijing weaned on dialectical materialism have done their homework while building their alliance attuned to the 21st century.